The Palace of Eternal Youth, a masterpiece of traditional Chinese opera, stands as one of the most celebrated works in the history of Kunqu opera, later adapted into Peking Opera, captivating audiences with its profound exploration of love, politics, and the transient nature of power. Originally written by Hong Sheng (1645-1704), a renowned playwright of the Qing Dynasty, this 50-scene epic weaves a poignant tale of the tragic love between Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (Li Longji) and his consort, Yang Yuhuan (Yang Guifei), against the backdrop of the An Lushan Rebellion, a pivotal event that led to the decline of the Tang Dynasty.

Historical Background and Creation

Hong Sheng devoted over a decade to crafting The Palace of Eternal Youth, revising it three times between 1687 and 1688. Set during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the opera draws from historical annals and earlier literary works, such as Bai Juyi’s famous narrative poem "Song of Everlasting Regret" (Chang Hen Ge). However, Hong Sheng transcends mere historical retelling, infusing the story with philosophical depth by examining the conflict between personal desire and imperial duty, the corruption of power, and the karmic consequences of human actions. The play’s title, "Changsheng Dian," refers to the palace hall where Emperor Xuanzong and Yang Guifei vow eternal love, symbolizing both their bond and the fragility of their happiness.

Plot Synopsis

The opera unfolds in two acts, mirroring the trajectory of the lovers’ relationship and the political turmoil surrounding them. The first half celebrates their passionate romance: Yang Yuhuan, initially the wife of Emperor Xuanzong’s son, is summoned to the palace, captivating the emperor with her beauty and grace. She is elevated to the rank of Guifei (noble consort), and her family, including her ambitious cousin Yang Guozhong, gains significant influence. The lovers’ bond deepens as they enjoy a life of luxury, exemplified by the iconic "Palace Oath" scene, where they pledge eternal love under the stars on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, a traditional festival for lovers in China.

The second half shifts dramatically to tragedy as political tensions escalate. An Lushan, a powerful military governor with a grudge against Yang Guozhong, launches a rebellion, forcing the emperor and his court to flee the capital. During the chaotic retreat to Sichuan, the emperor’s soldiers, blaming Yang Guifei and her family for the crisis, demand her death to appease the gods and ensure the dynasty’s survival. Reluctantly, Emperor Xuanzong consents, and Yang Guifei is strangled at Mawei Slope. Devastated by her loss, the abdicates and spends his final years in solitude, haunted by memories of their love. In a transcendent finale, the lovers are reunited in the afterlife, where they reaffirm their vow, free from the constraints of mortal politics.

Character Analysis

The central figures are richly drawn, embodying complex human emotions and moral dilemmas. Emperor Xuanzong, portrayed as a ruler torn between his love for Yang Guifei and his responsibility to his people, represents the dangers of prioritizing personal desire over statecraft. Yang Guifei, while often depicted as a symbol of beauty and indulgence, is also portrayed as a devoted lover caught in the crossfire of political intrigue. Antagonists such as Yang Guozhong, whose corruption fuels public resentment, and An Lushan, whose ambition triggers rebellion, highlight the play’s critique of courtly politics. Supporting characters, the eunuch Gao Lishi and the maid Chen Hongniang, add depth, offering perspectives on loyalty, sacrifice, and the human cost of power.

Artistic Features in Peking Opera Adaptation

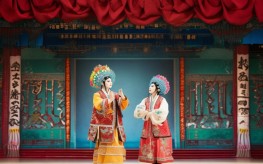

While The Palace of Eternal Youth originated as a Kunqu opera, its adaptation into Peking Opera enhances its dramatic impact through the latter’s distinctive vocal and performative styles. Peking Opera, known for its elaborate arias, acrobatic movements, and symbolic stagecraft, brings the story’s emotional intensity to life. Key elements include:

- Vocal Music: The opera uses Gubi (fixed-pitch tunes) and Xipi (slow-paced melodies) and Erhuang (fast-paced melodies) to convey characters’ emotions. For instance, Yang Guifei’s arias in "The Drunken Concubine" scene (though more iconic in another opera) adapt similar lyrical traditions to express her melancholy.

- Performance Techniques: Actors employ elaborate gestures (shoufa), facial expressions (mianbu), and stylized movements (shenfa) to depict inner turmoil. For example, the "water袖" (water sleeves) are used to convey grief or grace, while "翎子功" (pheasant feather dance) symbolizes nobility or agitation.

- Stage Design: Minimalist sets, such as a simple table or chair, evoke palaces, battlefields, and landscapes, allowing the audience’s imagination to fill in the details. Costumes, rich in embroidery and color, distinguish characters: Yang Guifei wears ornate robes in pink and gold, while Emperor Xuanzong’s attire emphasizes imperial authority in deep blue and red.

The table below contrasts Kunqu and Peking Opera adaptations of the play:

| Element | Kunqu Opera Version | Peking Opera Version |

|---|---|---|

| Vocal Style | Softer, more lyrical, with emphasis on melody | Stronger, more rhythmic, featuring high-pitched arias |

| Movement | Graceful, fluid, with subtle gestures | Dynamic, incorporating acrobatics and martial arts |

| Focus | Poetic lyricism and emotional subtlety | Dramatic tension and visual spectacle |

| Key Scenes | "Palace Oath," "Song of Everlasting Regret" | "Mawei Slope," "Reunion in the Moon Palace" |

Cultural Significance

The Palace of Eternal Youth transcends its historical setting to explore universal themes: the tension between love and duty, the corruption of power, and the quest for redemption. It also reflects Confucian values, such as filial piety and social order, while incorporating Taoist and Buddhist motifs of reincarnation and karmic justice. For Western audiences, the opera offers a window into traditional Chinese aesthetics, from its symbolic storytelling to its philosophical underpinnings, making it a bridge for cross-cultural understanding.

In English-language performances and scholarship, the opera is often rendered as The Palace of Eternal Youth or Everlasting Regret, with translators balancing fidelity to the original text with accessibility for non-Chinese speakers. Notable adaptations include productions by the Chinese Peking Opera Theatre and academic analyses that explore its parallels with Western tragedies, such as Romeo and Juliet or Antony and Cleopatra.

FAQs

What are the key differences between the Kunqu and Peking Opera versions of The Palace of Eternal Youth?

The Kunqu version prioritizes poetic lyricism and subtle emotional expression, with softer vocals and graceful movements, emphasizing the romance and melancholy of the story. In contrast, the Peking Opera version amplifies dramatic tension through stronger vocals, acrobatic performances, and elaborate stagecraft, focusing on the political conflict and tragic climax. For example, the Mawei Slope scene in Peking Opera features more intense physical acting to depict the soldiers’ fury and Yang Guifei’s despair, while the Kunqu version relies on nuanced vocal delivery to convey sorrow.

How does The Palace of Eternal Youth reflect traditional Chinese values and beliefs?

The opera embodies Confucian ideals through Emperor Xuanzong’s struggle between personal desire (his love for Yang Guifei) and imperial duty (protecting his dynasty). It also incorporates Taoist themes of harmony with nature, seen in the lovers’ garden scenes, and Buddhist beliefs in reincarnation, as the couple reunites in the afterlife. Additionally, the play critiques the Confucian value of "filial piety" when the soldiers demand Yang Guifei’s death, questioning whether societal order should override individual innocence. These layers make the opera a rich tapestry of traditional Chinese thought.