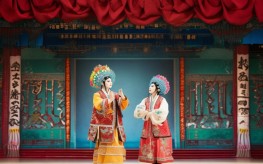

San Tang Hui Shen, often translated as "The Three-Hearings Trial," stands as one of the most iconic and beloved excerpts in the repertoire of Peking Opera. Rooted in the full-length traditional play Yu Tang Chun (The Spring of the Jade Hall), this piece has captivated audiences for over a century with its gripping narrative, exquisite artistry, and profound exploration of justice, love, and human resilience. As a quintessential example of Peking Opera’s dramatic and musical brilliance, San Tang Hui Shen showcases the harmonious integration of singing, recitation, acting, and acrobatics, embodying the essence of this traditional Chinese performing art.

Background and Origin

Yu Tang Chun originated from the Ming Dynasty vernacular novel The Three Words (San Yan), specifically the story "Yu Tang Chun Zhuan" (The Tale of Yu Tang Chun). The novel follows the tragic yet ultimately redemptive journey of Su San, a young woman forced into prostitution after being betrayed by her husband, Shen Aixin. Wrongfully accused of murdering Shen, Su San is imprisoned, faces torture, and is eventually brought to trial—a pivotal moment dramatized in San Tang Hui Shen.

The excerpt gained prominence in the Qing Dynasty, as Peking Opera troupes adapted it to highlight the emotional depth and technical skill of performers. Over time, San Tang Hui Shen evolved into a standalone piece, celebrated for its intense courtroom drama and the nuanced portrayal of its characters, particularly Su San, whose innocence and resilience become the focal point of the narrative.

Plot Synopsis

The story unfolds during the Ming Dynasty, when Su San, a former courtesan, is accused of poisoning her husband, Shen Aixin. After being wrongfully convicted and imprisoned, she is summoned for a retrial before three high-ranking officials: Pan Bizheng (Provincial Administration Commissioner), Liu Bingyi (Provincial Surveillance Commissioner), and Wang Jinlong (Provincial Surveillance Commissioner, incognito).

What makes the trial unique is the hidden identity of one official: Wang Jinlong is, in fact, Su San’s former lover, whom she had believed dead. Years prior, Su San and Wang, a poor scholar, had fallen in love and married. However, Wang was forced to flee after killing a ruffian who harassed Su San, leaving her vulnerable to exploitation by a brothel owner.

During the trial, Su San recounts her tragic story in arias and dialogue, detailing her suffering, wrongful accusation, and unwavering hope for justice. As Pan and Liu interrogate her, Wang Jinlong recognizes her and discreetly works to uncover the truth. Through clever questioning and hidden clues, he exposes the real culprits—Shen Aixin’s vengeful family and a corrupt official who framed Su San. In the end, Su San is exonerated, and she is reunited with Wang, bringing the story to a triumphant close.

Character Analysis and Artistic Elements

San Tang Hui Shen’s enduring appeal lies in its rich characterizations and the masterful use of Peking Opera’s performance conventions.

Key Characters

- Su San (Dan Role): Protagonist, portrayed by a dan (female role) performer, typically a qingyi (virtuous woman) specializing in graceful, restrained acting. Her arias, marked by lyrical melodies and poignant emotion, convey her innocence, sorrow, and quiet determination.

- Wang Jinlong (Lao Sheng Role): Su San’s lover, played by a lao sheng (older male role) actor. His performance balances authority (as a high-ranking official) with hidden tenderness, revealed through subtle glances and modulated vocal tones.

- Pan Bizheng and Liu Bingyi (Lao Sheng Roles): The other two trial officials, each with distinct personalities—Pan is stern and impartial, while Liu is more skeptical and sharp-witted. Their interactions add tension and humor to the drama.

Performance Techniques

- Singing (Chang): The opera features xipi (West Tune) and erhuang (Second Tune) melodies, two core musical systems in Peking Opera. Su San’s arias, such as "Su San Qi Jie" (Su San’s Seven Pledges), showcase vocal agility, with trills and vibrato expressing her anguish.

- Recitation (Nian): Spoken dialogue is delivered in stylized, rhythmic patterns, distinguishing between baihua (vernacular) for formal exchanges and yunbai (poetic recitation) for emotional moments.

- Acting (Zuo): Performers use highly codified movements to convey emotion. For example, Su San’s "kneeling walk" (gui bu)—shuffling forward on her knees—symbolizes her suffering and desperation, while the "water sleeve" (shui xiu) technique, where long sleeves flick or sway, amplifies gestures of grief or supplication.

- Acrobatics (Da): Though subtle in this excerpt, elements like the "wooden cangue" (yu jia)—a heavy neck collar worn by Su San—require precise physical control, highlighting the character’s oppression.

Costume and Symbolism

- Su San: Wears a red fan yi (criminal robe), symbolizing both her status as a convict and the passion she once felt for Wang. Her hair is disheveled, and she is shackled, emphasizing her vulnerability.

- Officials: Clad in elaborate guan pao (formal robes) with embroidered rank badges, their attire reflects authority and order, contrasting sharply with Su San’s tattered clothing.

Cultural Significance

San Tang Hui Shen transcends mere entertainment, offering insights into traditional Chinese values and societal structures. It critiques corruption and injustice within the judicial system while celebrating the triumph of truth and love. For audiences, Su San’s journey resonates as a universal tale of resilience, her unwavering faith in justice mirroring the human desire for redemption.

Moreover, the opera exemplifies Peking Opera’s role as a custodian of cultural heritage. Its preservation and performance today ensure that stories like Su San’s continue to bridge generations, connecting modern audiences to the artistic and moral traditions of imperial China.

Role and Performance Elements Summary

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Play Type | Excerpt from Yu Tang Chun (Peking Opera full-length play) |

| Genre | Historical drama with themes of justice, love, and resilience |

| Lead Role | Su San (Dan/Qingyi), emphasizing lyrical singing and graceful acting |

| Musical Style | Xipi and Erhuang melodies, featuring solos and ensemble recitative |

| Key Techniques | Water sleeve (shui xiu), kneeling walk (gui bu), stylized dialogue (nian) |

| Symbolism | Red criminal robe (passion/suffering), official robes (authority/order) |

FAQs

What is the historical origin of "San Tang Hui Shen," and how did it evolve into a standalone Peking Opera piece?

San Tang Hui Shen derives from the Ming Dynasty novel The Three Words, specifically the story of Su San. Initially part of the full-length opera Yu Tang Chun, it gained popularity in the Qing Dynasty as troupes recognized its dramatic potential. Over time, the trial scene was extracted and refined to highlight the dan role’s vocal and acting skills, eventually becoming a standalone excerpt. Its focus on emotional depth and technical virtuosity ensured its status as a classic, performed widely in theaters and taught in Peking Opera schools.

How does Peking Opera’s unique performance style enhance the storytelling in "San Tang Hui Shen"?

Peking Opera’s integration of singing, recitation, acting, and acrobatics creates a multi-dimensional narrative. For instance, Su San’s arias (chang) convey her inner turmoil, while stylized movements (zuo), like the kneeling walk, visually depict her suffering. The contrast between her humble costume and the officials’ elaborate robes underscores power imbalances, and rhythmic dialogue (nian) builds tension during the trial. These conventions transform a simple courtroom drama into a rich, immersive experience, allowing performers to communicate complex emotions and themes without relying on realistic sets or props.